MEXICO CITY — The legislature of Mexico City approved the most ambitious rent control law since the 1940s Thursday, limiting rent increases to the rate of inflation in the previous year.

Rents in the vast city of 9 million inhabitants were essentially frozen in the 1940s, and remained so for decades on older buildings. Those controls were largely lifted in the 1990s.

The new law will also require landlords to register all rental agreements with the city. It was unclear whether the new law will allow landlords to charge more for improvements on their properties.

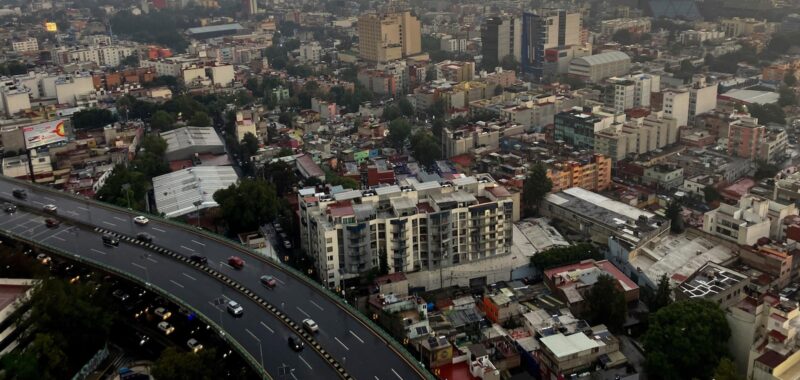

Mexico City, like many around the world, had seen complaints that rents were shooting up because of digital nomads and short-term rentals. But it appears that largely affected only a handful of touristy neighborhoods near the center of the sprawling metropolis.

“A lot of people with higher incomes are willing to pay more for housing, both by buying and renting it,” said legislator Martha Soledad Avila Ventura of the governing Morena party. “Moreover, short-term rentals on the internet have made it a question of profit, which has resulted in the expulsion of the traditional residents of the capital.”

In recent years, a shortage of land and saleable properties has sparked a cut-throat real estate market in which property prices increased well above the rate of inflation.

However, the new law doesn’t address the city’s real problem: a shortage of housing units. Legislators estimated there are about 2.7 million houses and apartments in the city, but it needs about 800,000 more.

The city has long depended on private developers to build housing, and it is unclear whether the new law could discourage investment in residential construction.

Rent control has a complex history in Mexico City. Under the 1940s fixed-rent laws, inflation quickly decimated rents in real terms, resulting in people paying pocket change for apartments. Landlords gradually abandoned the buildings, because the rental income was insufficient to pay for even routine maintenance.

Old rental laws also made it hard to evict tenants for non-payment and gave some tenants the right of first refusal if the units they lived in were put up for sale. That caused a distortion in rental markets, with many landlords preferring to rent to foreigners, who were viewed as less likely to invoke those protections.

In the 1950s and ’60s, the government built several large housing complexes in the city, though rarely for renting. Those apartments were almost always put up for sale to new buyers once completed.

The current city government has no real plans for constructing large numbers of its own rental units, nor does it have the money or construction know-how to do so.

Moreover, almost any new construction is out of reach for the poorest residents. Mexico’s minimum wage is equivalent to about $1.50 per hour and the median wage is only about $4 per hour.

President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum, also of the Morena party, has said she hopes to implement a rent-to-buy program. Poorer tenants would pay a reduced-rate rent, and if they obtained a government housing loan, the rent they paid previously would be applied to the purchase price.

She also wants the federal housing agency, which is financed through payroll deductions funding individual accounts for each worker, to start building housing itself. At present, the agency acts largely as a financing agency, granting loans to acquire homes built by private developers.