Most workplaces still fail to accommodate neurodivergent employees—discover how neuroinclusive design can transform offices into spaces that support focus, well-being, and productivity for all.

In the 1990s, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) finally tackled physical barriers in workplace design. This legislation changed how we design building by requiring features like ramps, wider doorways and hallways, and accessible restrooms. But even with that progress, we’re still failing the millions of people with sensory and cognitive challenges.

About one in five people are neurodivergent, yet most spaces simply aren’t built with their needs in mind.

What does this failure look like in workplace design? Consider these scenarios:

Kai steps off the packed elevator into the lobby of his new office. His heart is pounding. Sounds assault him from all sides. Conversations echo off hard floors, phones ring nonstop, and the fluorescent light feels like it is pulsing through his body. He searches in vain for refuge among countless rows of identical gray desks. There is no landmark to guide him.

Zara is still struggling in the new open office. She flinches every time someone passes behind her workstation. The enormous company logos plastered across the walls flash in her peripheral vision, and conversations between her coworkers on calls are overwhelming. She turns up the music playing through her headphones and wonders how she is supposed to focus.

Jamie gazes at the blank white walls of the meeting room, trying to concentrate on a colleague’s presentation. Bright overhead lights make the text on their laptop screen almost illegible. The sterile room lacks plants or art, and there is no visual connection to the outdoors. The seats around the table are tightly packed and there is no space to stand, move, or fidget without impacting others.

These aren’t isolated cases. Millions of employees struggle with sensory issues at work. Most offices just aren’t built to accommodate the spectrum of people’s diverse sensory needs. This needs to change.

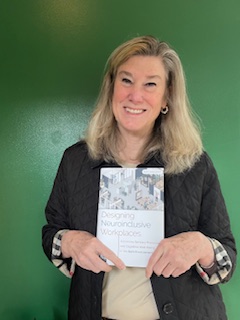

My new book, Designing Neuroinclusive Workplaces: Advancing Sensory Processing and Cognitive Well-Being in the Environment (Wiley, March 2025), describes solutions for this problem. It weaves together client stories, interviews with inclusion experts, profiles of well-known innovators and creators, and personal insights from our team to create a practical guide for organizations. The ultimate goal is simple: create environments that enable everyone do their best work.

The solutions aren’t complicated, but they do require some changes to our design process. The book features many detailed case studies of successful neuroinclusive workplaces. Here are two examples from KPMG and Arup that show these ideas in action.

KPMG’s Manhattan Vision

For the headquarters of its U.S. firm, KPMG wanted a different approach. Working with HOK’s design team, they set out to create an inclusive workplace at Two Manhattan West. What made it work? Business Resource Groups and neurodiversity experts were part of the planning process from the start.

Instead of assigned seating, the design organizes the space into flexible neighborhoods that give employees a home base while maintaining choice and mobility. The design offers varied work settings for different tasks, from quiet focus areas to collaborative zones, with careful attention to sensory-considerate furniture, materials, and finishes. The team collaborated with HOK’s Experience Design group to ensure graphics enhanced the space without becoming overwhelming. Active design features, including a connecting staircase across all 12 floors, encourage movement and community.

The project, which is now under construction, demonstrates that neuroinclusive design can work at scale while creating an engaging, high-performance workplace that supports in-person collaboration and individual focus work.

Engineering Excellence at Arup Birmingham

At Arup’s new Birmingham office, the engineering firm recognized that their workforce likely includes a higher-than-average percentage of neurodivergent individuals. HOK’s team worked with them to develop a sophisticated design incorporating six distinct work modalities: concentrate, contemplate, commune, create, congregate, and convivial.

The workplace features thoughtful spatial planning that maximizes natural light and views, innovative acoustic solutions, and adaptive lighting systems that respond to individual needs. The results are compelling. Employees report reduced cognitive fatigue and increased comfort, and Arup reports that office attendance is up by 10%.

Best of all, the office has become a place where Arup’s people want to be. One engineer noted he no longer experiences headaches, fatigue, or anxiety from being in the office—the ultimate validation of the design’s success.

Moving Past Misconceptions

We occasionally get pushback when we talk about neuroinclusive design. People worry about renovation costs or think offices must become entirely stimulation-free. But that’s not true. These solutions don’t require expensive overhauls—they just take smart planning and strategic choices from the start.

These case studies show that neuroinclusive workplaces deliver real results—from KPMG’s successful transformation to Arup’s measurable increases in employee well-being and attendance. This isn’t just aspirational—it’s achievable through thoughtful design choices that create workplaces that work for everyone.